bonsai log 01

the roots of a course

Believe it or not, I have a day job. I'm a lecturer at Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

I'm two weeks out from welcoming hundreds of students to the course I'm convening this term: Quantitative Reasoning, 1015SCG. In the spirit of experimentation I am also keeping public notes about how I'm building the course — and how I feel like it's going!

My first guiding principle is to be relentlessly practical — so I'll focus first on what I'm doing, and avoid over-theorising or making silly asides until I get to the end!1

Lecture 1: Numbers

This lecture will have roughly two halves:

an Admin and Introduction section, and

a quick refresher about essential2 mathematical operations.

The Admin section will cover the course's structure, Canvas website, assessment dates, and overview of topics. But I'm reminding myself here that I'd like to add in two things:

Not just “you can contact your Program Officer for admin questions”, but the names and emails of the relevant people.

Dates to drop the course without penalty and alternative courses to take.

Students have enough admin burden, especially in their first week of their first term; a little bit of pre-work on my end for 500 students’ frantic searching is a pretty good trade-off.

The Introduction section? I'm having a big think about that, especially to avoid over-theorising. I want to strike the balance between giving students practical help with skills they need practicing — and sparking their curiosity with the motivation they need to keep going! So under this section I'll quickly talk to:

Their previous experience with maths. We've all grown up in a culture where some people “just get maths” because they're “smarter”. I'll propose an alternative story: maths is a rather strange place with a strange language and toolset, but one with lots of power for both good and bad. When you're new to some place you'll be stranded and confused — that doesn't make you stupid, silly, or worth any less! Instead you just need to take time and get to know your surroundings!

What numbers are for. I'll show them a photo I just love (under the list) of a shower tap with a feature I've never seen anywhere else: temperature markings! Those numbers, I'll point out, are actually a communication. They tell you what to expect (in this case how hot the water will be). Why don't we have those taps at home? Well, because everyone's hot and cold water are at different temperatures, and you couldn't possibly expect the tap to tell you the right temperature most of the time! (The tap picture was taken on an overnight ferry, with hot and cold water clearly plumbed from some central, controlled tanks.) So that's what numbers do: they help you keep track of the things you can quantify, as part of people's never-ending efforts to make life better for each other.

What an equation is: our chief trick in maths is starting out knowing that one number (possibly unknown) will be the same as another. And if we do the same operations on either side of an equation, those numbers will still be the same! That motivates us to learn about core operations in mathematics, as well as their inverses.

Depending on how the class is going, I might delay point 3 until after the break!

The next section really is a refresher on the core operations: addition and subtraction, multiplication and division, exponentiation, and logarithms. But I'll probably use “inverses” and “solving equations” to keep motivating ourselves: we're not just pushing symbols around, we're working from the information we have to calculate the answer we need!

Thank you, dear reader, for following along! The process of writing out this little log has reinforced several things in me.

Firstly: all knowledge really is social. All learning really is social. I felt so much firmer and happier about what I'd be teaching after having written it out to an audience, even a contingent or hypothetical audience.

I don't think this is trivial. Every story of humanity’s origins emphasizes that humanity's first and highest purpose is relationship — whether religious stories about humanity relating to God, or secular stories about humanity's crucial evolutionary advantage being our complex communication and social ordering that enables global-scale interactions. So why shouldn't relationship be foundational to our brains? To all our cognitive acumen and throughput? It makes sense, if our brains are wired for connection, that connection would be the first and best thing to fire up our brains — that I'd always find myself thinking and working most clearly with.

Secondly: that knowing, and especially teaching, is about accomplishing the minimal. When I was tossing several possible frameworks for this post around in my head I got nowhere. But then I decided: I'll just say what I'm teaching, and then one or two points about why. And that was it!

That's why I'm titling this a “bonsai” log3. Over the past year I've wrestled, existentially at times, with: what am I doing as a university lecturer? How does anyone ever learn anything from what I teach? It's all at once so arcane and complicated and so theoretical and impractical. The analytical formula for how much acid to put into my swimming pool to neutralise its pH — it is at once so difficult that I bungled it in my second year chemistry last year, and so contrived it's not remotely accurate (for example, it doesn't account for salt concentration!).

I've had to start by accepting that I simply can't teach my students their jobs. You learn how to a job by doing a job. (Otherwise companies would save untold billions on onboarding by only ever hiring candidates who didn't need onboarding.) They'll probably graduate into a job market applying for jobs that didn't exist when I taught them! But in that case, what am I doing? Well, it follows, I'm not teaching my students everything they need to know. Rather, I'm teaching them one thing. Teaching them the one thing with the most analytical bang for their student-fee (and prime-of-their-life-time) buck, the one thing they most need to learn from classes rather than from experience.

It's the ambition of bonsai: a smallest-possible tree. Not brambling branches aiming to cover every edge case and rare niche. Maybe other lecturers are good at that sort of thing, but I find myself drawn more than ever to honing just a small, crisp, fine rendition of the beauty that is truth. That's the goal. That's good enough.

My zeroth principle: if I'm emphatic about something, I should immediately say what the alternative would have been, to hold myself accountable and own what I say as a strategic, thoughtful choice.

I'll do my best to say “essential”, “foundational”, or “core” instead of “basic”, “beginner”, or (especially!!) “easy” — that is, the fact that some skills are prerequisites to others never implies that they take less effort or (especially!!) intelligence to learn. I'll be teaching students who still aren't sure what it means to “move a plus across the equal and turn it into minus”. The last thing I need is self-doubt making their job and mine harder.

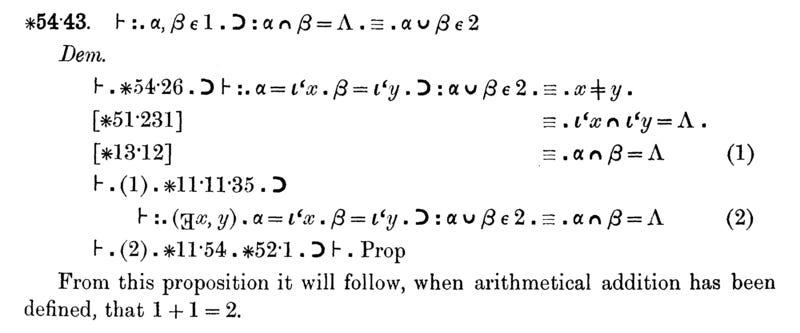

Not only is this solid social-emotional learning, it's just facts. In maths (as in life) “essential” isn't always “easy”. I'll drive this home with the following screenshot from Whitehead and Russell’s Principia Mathematica:

“1+1=2” is foundational maths; but it can be made very, very uneasy.

I am forever indebted to the Software Carpentries for teaching me to never say “easy”. “Just” (as in, “just move the plus across”) is also a four letter word.

It's a bonsai log because trees are what we made logs out of. What, did you expect to escape my post without a pun? No hope. It's puns all the way down.

"I'm not teaching my students everything they need to know. Rather, I'm teaching them one thing."

Excellent. This is good for every single form of communication, I think. There's an element of self-trust that you can deliver one good thing as well as community trust that they will be able to hold onto that one thing and then go get the others.